- Home

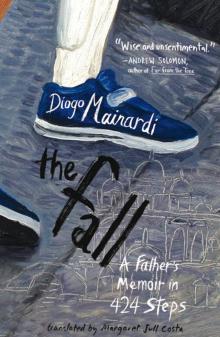

- Diogo Mainardi

The Fall Page 8

The Fall Read online

Page 8

I freed myself from my debt to Tito because I was represented in the Venice courts by Romolo Bugaro, a novelist disguised as a lawyer from Padua.

355

During the first ten years of his life, Tito cost me 3,497,916 eggs.

From that day on, he began to produce his own eggs, like Neil Young’s son on his farm.

356

In the last volume of In Search of Lost Time, the Narrator is filled with a sense of happiness because the memory of his walks over the uneven paving stones of Venice renders him “unalarmed by the vicissitudes of the future” and indifferent to “the word ‘death.’ ”

On the walk back from the Fondamenta delle Zattere, after receiving Romolo Bugaro’s phone call, I too was filled with a sense of happiness. From one moment to the next, Tito’s future had ceased to depend upon me. I was free to die.

357

(Picture Credit 1.20)

358

In the previous image: Ezra Pound’s funeral in Venice.

359

In 1945, Ezra Pound was arrested and charged with treason for his radio broadcasts about Jewish parasites.

After twelve years in St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, he was released and moved back to Venice, where he remained until his death.

I spent less time in Rio de Janeiro than Ezra Pound spent in St. Elizabeth’s.

After only eight years, I began to think about going back to Venice and remaining there until my death.

360

Tito was fine in Rio de Janeiro. Nico was fine in Rio de Janeiro. Anna was fine in Rio de Janeiro. I was fine in Rio de Janeiro.

However, just as we always started counting from zero again whenever Tito stumbled and had to stop walking, Anna and I needed to go back to Venice and take up our lives where they had left off.

361

I’m looking now at the photos of our last months in Rio de Janeiro.

Tito celebrating his birthday in a barbecue restaurant. Nico playing football at the Flamengo football school. Tito with his walker, following a carnival troupe. Nico spotting a whale from the window of our apartment. Tito on his way to school on his tricycle. Nico watching the removal of a corpse from the trunk of a car.

We were fine in Rio de Janeiro. We were ready to leave.

362

363

In the previous image: Tito on his tricycle.

The tricycle was Tito’s fourth mode of transport.

364

We disembarked in Venice on 4 August 2010.

365

Mark Twain disembarked in Venice on 20 July 1867.

He wrote:

What a funny old city this Queen of the Adriatic is!

… If you want to go to church, to the theatre, or to the restaurant, you must call a gondola. It must be a paradise for cripples, for verily a man has no use for legs here.

366

Venice was a paradise for my cripple.

For the first time, Tito could move around freely, by vaporetto.

Contrary to Mark Twain, he also used his legs.

Accompanied only by someone we hired to help him up and down the bridges, Tito went for daily four-hour walks with his walker, passing churches, theatres and restaurants.

367

According to Mark Twain, Venice by night seemed “crowned once more with the grandeur that was hers five hundred years ago.” In the shadows, it was easy to imagine the city with its Desdemonas and its Shylocks, with its “plumed gallants and fair ladies,” with its “noble fleets and victorious legions returning from the wars.”

By day, though, Venice showed only signs of its fall from power. Mark Twain described it as “decayed, forlorn, poverty-stricken, and commerceless — forgotten and utterly insignificant.” In the glare of day, the Queen of the Adriatic looked like “an overflowed Arkansas town.”

368

Tito walked through Venice exactly as if he were walking through an overflowed Arkansas town, oblivious to Venice’s glory or its fall from power. What mattered to him was being able to walk alone. Paradise was a place in which Tito could walk without my help.

369

370

In the previous image: Tito and Nico during a flood in Venice.

371

Christopher Nolan had cerebral palsy.

He published his memoir, Under the Eye of the Clock, when he was only twenty-two years old.

When his book won a prize, he remarked: “You all must realize that history is now in the making. Crippled man has taken his place on the world’s literary stage.”

372

I was also working on a memoir about Tito.

My plan was to end the memoir with the story of an ascent of Mount Everest, which Tito would conquer three hundred and fifty-nine steps at a time.

My crippled man would take his place on the world’s stage. History in the making.

373

Christopher Nolan was born mute.

During his early years, he could communicate only by looking up. When he did that, his parents knew that he was saying “Yes.”

That’s right: all he could say was “Yes.”

374

When he was eleven, Christopher Nolan’s father strapped a “unicorn stick” to his head.

From that moment on, Christopher Nolan began to communicate in writing, tapping with the stick on the keyboard of a typewriter.

375

(Picture Credit 1.21)

376

In the previous image: Christopher Nolan and his father, Joseph Nolan.

377

In his memoir, Christopher Nolan described how the other boys at Mount Temple School in Dublin saw him.

They called him “weirdo,” “eejit” and “mental defective.” They wondered “if the cripple wore a nappy.” They discussed his “lack of intelligence.” They decided he shouldn’t be in a normal school.

378

Christopher Nolan’s isolation at Mount Temple School inspired R.E.M. to write a shamelessly sentimental song, asking: Why the other kids were always looking at him? Why did they laugh at him? What could he say? What could he do?

379

After seeing him every day, the boys at Mount Temple School eventually got used to Christopher Nolan.

It was the same with Tito.

The newsagent in Campo San Vio saw him every day. The old greengrocer saw him every day. The barber saw him every day. My wife’s friend saw him every day. The man with the two dogs saw him every day.

The inhabitants of our overflowed Arkansas town got used to Tito.

380

My plan to conquer the world with Tito three hundred and fifty-nine steps at a time soon collapsed.

Now my one goal was to limit myself to a small area that went from the Ponte dell’Accademia to Campo della Salute and was bounded by the Grand Canal and by the Fondamenta delle Zattere.

Tito had memorized all the uneven paving stones in our “town.” His knowledge of those uneven paving stones kept him from falling. Instead of forging new paths, I wanted him to forge only old paths. Instead of entering unknown territory, I wanted him to enter only known territory.

My world now ended wherever Tito’s steps ended.

381

As Gertrude Stein said of Ezra Pound: “[He] still lives in a village and his world is a kind of village,” and the same was true of me.

382

383

In the previous image: Tito on the Fondamenta delle Zattere.

During the autumn and winter, he could walk to school on his own, using the Venice Marathon ramps, which the city council kept on the bridges especially for him.

384

At Mount Temple School, Christopher Nolan studied with members of U2.

They dedicated a song to him, entitled “Miracle Drug.”

385

The song is a homage to the medicine that eased Christopher Nolan’s spasticity, helping him to type with his head.

The name of the medicine: Liores

al.

386

In “Miracle Drug,” U2 quote from the Gospel according to Matthew: “I was a stranger and you took me in.”

The quote comes from the passage about the Final Judgement in which Jesus Christ, like Josef Mengele, sends off to the right those who deserve to be saved and to the left those who deserve to burn in everlasting fire.

According to U2, the scientists and doctors who developed Lioresal deserved to enter the Kingdom of Heaven.

387

Tito never took Lioresal. He never took any medicine. No one was capable of developing a medicine that would prove useful to him. Christopher Nolan’s miracle drug was developed ninety years ago. People with cerebral palsy are still being treated with drugs developed ninety years ago.

388

(Picture Credit 1.22)

389

In the previous image: Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Lou Costello is transformed into a laboratory mouse.

390

Two years after Tito was born, scientists at the Medical College of Georgia placed stem cells in laboratory mice with induced cerebral-palsy symptoms and succeeded in achieving a partial improvement in their motor skills.

391

The results of the first experiments with laboratory mice led to stem cells being seen as a miracle cure.

In China, Russia, Costa Rica, in the Dominican Republic, in Turkey and in Cyprus, all kinds of medical centers sprang up, promising a cure for cerebral palsy with stem cells drawn from the skin, the spinal cord, from blood, from fat, from animal tissue, from placenta and from aborted fetuses.

According to a study carried out in 2008, the average cost of such treatments was $21,500.

392

Eleven years after Tito was born, an article published in the Scientist warned of the risks of “stem cell tourism.”

According to the authors of the article, people with cerebral palsy who travelled to those medical centers in search of a miracle cure were exposing themselves to “unproven, and potentially harmful therapies.”

The article described the doctors who offer stem-cell cures as “clinical charlatans” and “fraudulent.”

393

Christopher Nolan’s miracle drug was also fraudulent.

He died shortly before his forty-fourth birthday, with a sliver of salmon stuck in his throat.

To go back to Tommaso Rangone: the food that proved most harmful to Christopher Nolan’s health was salmon.

394

(Picture Credit 1.23)

395

In the previous image: Tommaso Rangone above the doorway of the church of San Giuliano.

The sculpture is by Jacopo Sansovino. It dates from 1554.

Tommaso Rangone is holding a sprig of guaiacum, the main ingredient in his miracle cure for syphilis.

396

In his memoir, Christopher Nolan frequently compares himself to James Joyce.

One wrote about cerebral palsy, the other about general paralysis caused by the syphilis bacterium.

397

James Joyce’s Dublin, like Tommaso Rangone’s Venice, was peopled by syphilitic sailors, syphilitic soldiers and syphilitic prostitutes.

In Ulysses, James Joyce used the morbid paralysis caused by the syphilis bacterium as a symbol of the intellectual and moral paralysis of his time. The episode in Bella Cohen’s brothel — which he himself described as being written in “the rhythm of locomotor ataxia” — is the rhythm that best represents that paralyzed world.

Tito was my Bella Cohen’s brothel.

398

The theme of Ulysses is paralysis. The theme of Finnegans Wake is the fall.

There is the fall of Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker — in Phoenix Park. There is the fall of Humpty Dumpty — the egg. There is the fall of Shaun — into the river. There is Shaun’s other fall — also into the river. There is the fall of Finn MacCool — while skating. There is the fall of Eve — in the Garden of Eden. There is the fall of Issy and the fall of Troy.

No one falls better than James Joyce. Apart from Lou Costello.

399

There is another fall in Finnegans Wake: a drunken Tim Finnegan falls down the stairs and dies.

Then he comes back to life, like Tito.

400

In Finnegans Wake, James Joyce based himself on Giambattista Vico’s theory, according to which, “History follows set phases, and the law that governs it is repeated eternally.” For Giambattista Vico, humanity moves from the Age of Gods to the Age of Heroes, from the Age of Heroes to the Age of Men, from the Age of Men to the Age of Gods, and so on, endlessly repeating the same cycle of birth, progress, decline and resurrection.

That’s what Giambattista Vico’s storia ideale eterna is like: circular.

401

Now Tito and I are in Campo Santi Giovanni e Paolo.

I want to show him Venice Hospital. I want to return — in circular fashion — to the place of his birth. I want to relive his first fall.

402

Tito walks alone to Venice Hospital. I walk beside him, ready to catch him if he falls.

403

I count Tito’s steps as if I were reciting Dante:

Uno … Due … Tre … Quattro … Cinque … Sei …

Sette … Otto … Nove … Dieci … Undici … Dodici …

Tredici … Quattordici … Quindici … Sedici …

404

Tito and I pass the statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni.

In The Stones of Venice, John Ruskin wrote:

I do not believe … that there is a more glorious work of sculpture existing in the world than that equestrian statue of Bartolomeo Colleone [sic].

405

406

In the previous image: the equestrian statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni by Andrea del Verrocchio.

The photograph was taken by Tito.

407

If Andrea del Verrocchio made the most glorious equestrian statue in the world, then I can say that I made the most glorious club-footed* boy in the world.

(* The Portuguese term for clubfoot is pé equino or “horse foot.”)

408

Tito continues to ride toward Venice Hospital:

… Duecentododici … duecentotredici …

duecentoquattordici … duecentoquindici …

duecentosedici … duecentodiciasette …

409

After two hundred and eighteen steps, Tito stumbles and almost falls on the uneven paving stones in Campo Santi Giovanni e Paolo.

I catch him before he falls and start counting again from zero.

410

In his final poem, entitled “Wild Broom,” Giacomo Leopardi describes an apple falling onto an ants’ nest and destroying in an instant the results of the ants’ vast labor, so painstakingly achieved.

I am Tito’s ant. His falls are a constant reminder of the precarious, temporary nature of everything I have tried to build.

411

Now Tito and I are standing before the Scuola Grande di San Marco, the entrance to Venice Hospital.

I show him the finest sculpture on the façade, The Healing of Anianus, in which Mark the Evangelist is applying his miraculous cure to the cobbler Anianus’s wound.

412

413

In the previous image: The Healing of Anianus.

The sculpture dates from 1488. It was made by Tullio Lombardo.

Tullio Lombardo was the son of Pietro Lombardo.

The photograph was taken by my son Tito.

414

Just as Pietro Lombardo created the Scuola Grande di San Marco with his son Tullio, I am writing this book with my son Tito.

This is all I can create.

415

Tito and I go up the disabled ramp and into the Scuola Grande di San Marco.

416

We pass the porter’s lodge of Venice Hospital and cross the old atrium of the Scuola Grande di San Marco, now deserted.

; 417

Trecentocinquantaquattro … trecentocinquantacinque

… trecentocinquantasei … trecentocinquantasette …

trecentocinquantotto … trecentocinquantanove …

418

We reach the cloister where I saw Tito for the first time, in an incubator, with a tube up his nose and with his face green.

419

420

In the previous image: Tito in the Dominican cloister.

421

When I saw Tito in the incubator on the day he was born, I knew that I would always love and help him.

Since then, nothing has changed.

I will always love him. I will always help him.

422

In 1483, Pietro Lombardo and his son Tullio Lombardo were commissioned to produce a sculpture of Dante Alighieri for his tomb in Florence.

They portray Dante Alighieri in meditative mood, his hand cradling his chin, as he composes the Divine Comedy.

423

I continue to count Tito’s steps as if I were reciting Dante Alighieri:

The Fall

The Fall