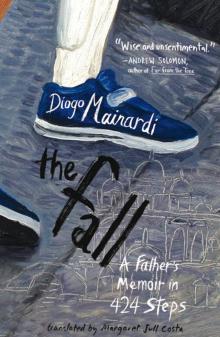

- Home

- Diogo Mainardi

The Fall

The Fall Read online

PRAISE FOR THE FALL

“A wise and unsentimental description of what it is like to be a parent to a child with cerebral palsy — an episodic portrait of a very intimate paternal journey.”

— ANDREW SOLOMON, National Book Award–winning author of Far from the Tree and The Noonday Demon

“The Fall, Diogo Mainardi’s remarkable celebration of his son Tito, who was born with cerebral palsy because of a doctor’s negligence, is intensely moving, rational, literate, and an absolute joy to read from start to finish.”

— JOHN BERENDT, New York Times best–selling author of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil and The City of Falling Angels

“The Fall is a moving portrait of a relationship with a child and a place. It is a rare book: by turns heartbreaking, angry, and lyrical.”

— EDMUND DE WAAL, author of The Hare with Amber Eyes

“The Fall is a memoir from Diogo Mainardi, the great Brazilian journalist/novelist, tracing the life and sufferings of his son Tito. Due to the gross negligence of the hospital in which Tito was born, he has been afflicted with cerebral palsy. Tito’s story is told in 424 parts, two or three per page, by turns angry, loving, and poetic, that mirror the number of steps Tito takes between their apartment and that hospital, the greatest number of steps Tito has ever taken without falling down. Along the way, Diogo ruminates about art history, philosophy, literature, and what it is to love someone unconditionally, through every tribulation that arises, and at whatever cost.”

— CONRAD SILVERBERG, Boswell Book Company (Milwaukee, WI)

“Other Press has done it again. What a fabulously intricate and idiosyncratic memoir. And what a gift to readers who, but for this book, could not conceive a parent so ferociously loving — and continually delighting in — his disabled child.”

— ELIZABETH ALEXANDER, University Book Store (Seattle, WA)

“Much like biblical passages I have attempted to read, I did not know what I was reading when I started The Fall. The truth, to borrow Emily Dickinson’s turn of phrase, dazzled me gradually. This is a potent prayer from a father to a son, from a father to his new god, this firstborn son with cerebral palsy. It is a gorgeous love letter, comforting and dismaying as any psalm.”

— VERONICA BROOKS-SIGLER, Octavia Books (New Orleans, LA)

“I read The Fall in a sitting; when I looked up, the world seemed a brighter place. It’s a memoir, a secret history, an argument against the accidental, but more than anything, it’s an astonishing portrait of a parent’s love. This is a tell-everyone-you-know-to-read-it book.”

— STEPHEN SPARKS, Green Apple Books (San Francisco, CA)

Copyright © Diogo Mainardi 2012

Originally published in Portuguese as A Queda:

As memórias de um pai em 424 passos in 2012

by Editora Record, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

English translation copyright © Margaret Jull Costa 2014

First published in English in 2014 by Harvill Secker, London.

Production Editor: Yvonne E. Cárdenas

Text Designer: Julie Fry

Grateful thanks to Faber and Faber for permission to reproduce an excerpt from Ezra Pound, ABC of Reading, copyright © 1934 Ezra Pound, and to New Directions, acting as agent, for permission to reproduce an excerpt from a letter written by Ezra Pound to Lina Caico, held in the Lina Caico Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, copyright © 2013 by Mary de Rachewiltz and Omar S. Pound.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 2 Park Avenue, 24th Floor, New York, NY 10016. Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows: Mainardi, Diogo, 1962–

[Queda. English]

The fall : a father’s memoir in 424 steps / by Diogo Mainardi; translated from the Portuguese by Margaret Jull Costa.

pages cm

“Originally published in Portuguese as: A Queda: As memórias de um pai em 424 passos in 2012 by Editora Record, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.”

ISBN 978-1-59051-700-0 (hardback) — ISBN 978-1-59051-701-7

1. Tito, 2000 — Health. 2. Mainardi, Diogo, 1962– 3. Paralysis, Spastic, in children — Biography. 4. Fathers and sons — Biography. I. Costa, Margaret Jull, translator, II. Title.

RJ496.S6M3514 2014

616.8′420092 — dc23

[B]

2014005571

v3.1

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

First Page

Picture Credits

1

Tito has cerebral palsy.

2

I blame Tito’s cerebral palsy on Pietro Lombardo.

In 1489, Pietro Lombardo designed the Scuola Grande di San Marco. And it was the Scuola Grande di San Marco designed by Pietro Lombardo that brought about Tito’s cerebral palsy.

3

On 30 September 2000, my wife and I set off for Venice Hospital in Campo Santi Giovanni e Paolo. Our son would be born that day. My wife’s name: Anna. Our son’s name: yes, that’s right, Tito.

When we reached Campo Santi Giovanni e Paolo, next to the statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni, Anna said: “I’m really worried about the birth.”

She had expressed the same fear in previous weeks, because Venice Hospital, now looming before us, was known for its medical errors.

I studied its façade for a moment.

Venice Hospital moved into the Scuola Grande di San Marco in 1808. The façade, designed by Pietro Lombardo in 1489, became the hospital’s main entrance.

I said: “With a façade like that, I could even accept having a deformed child.”

4

Venice Hospital made a mistake during Tito’s birth. That mistake brought about his cerebral palsy.

5

Ezra Pound, ABC of Reading:

A few bits of ornament applied by Pietro Lombardo … are worth far more than all the sculpture and “sculptural creation” produced in Italy between 1600 and 1950.

I went further than Ezra Pound. What I said to my wife, as I contemplated the façade of the Scuola Grande di San Marco, can only be interpreted thus: “Pietro Lombardo is worth far more than my son’s cerebral palsy.”

6

(Picture Credit 1.1)

7

In the previous image: Campo Santi Giovanni e Paolo.

The painting is by Antonio Canal — or Canaletto. It dates from 1725.

Anna and I, clinging to each other like Siamese twins, are standing by the statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni, on our way to the Scuola Grande di San Marco, the entrance to Venice Hospital, where Tito will be born.

8

How did I end up in a painting by Canaletto?

I was always there. And always will be there. The Canaletto painting is my personal nativity. It captures the moment when my destiny was revealed. Ever since Tito’s birth, on 30 September 2000, I have become a miniature man, without face or identity, just as I am in Canaletto’s painting. What marks me out is fatherhood. I am merely a man eternally accompanying his wife to the birth of their son.

I am Tito’s father. I exist only because Tito exists.

9

As well as praising Pietro Lombardo in ABC of Reading, Ezra Pound also praised him in The Cantos.

In particular, in Canto XLV, entitled “With Usura.”

Lines 27–28:

Came not by usura …

10

Usury, according to Ezra Pound, was a “sin against nature.” It had the power to corrupt humanity, preventing art from flourishing.

In Canto XLV, Pietro Lombardo symbolizes the idea of artistic beauty. Evil, represented by usury, is incapable of creating Good, represented by the architecture of Pietro Lombardo.

Looking at the Scuola Grande di San Marco before Tito’s birth, I was in the grip of the same stupid aestheticism as Ezra Pound.

Venice Hospital was known for its medical mistakes. Instead of going to a safer hospital, in Mestre or in Padua, I merely made a joke about the possibility of having a deformed child.

I could only associate the perfect art of Pietro Lombardo with an equally perfect birth. Because Good, represented by the architecture of Pietro Lombardo, would be incapable of creating Evil, represented by a bungled birth.

11

Ezra Pound, Canto XLV, line 42:

Usura slayeth the child in the womb

The person who nearly slew Tito in the womb by asphyxiation was the hero of those lines by Ezra Pound, Pietro Lombardo.

12

From Ezra Pound to Xbox.

The hero of the game Assassin’s Creed II, Desmond Miles, goes back in time and takes on the identity of an Italian nobleman from the late fifteenth century, Ezio Auditore da Firenze, who scours Venice in order to eliminate the murderers who asphyxiated his father. One of the places he has to pass is the Scuola Grande di San Marco.

I am the Desmond Miles of cerebral palsy. I return to the Venice of the late fifteenth century and, like Ezio Auditore da Firenze, I scour the Scuola Grande di San Marco in search of clues that will lead me to the murderers who asphyxiated Tito.

13

(Picture Credit 1.2)

14

In the previous image: Ezio Auditore da Firenze outside the Scuola Grande di San Marco, poised and ready to destroy his enemies.

The clues that allow you to continue the game (press button Y to get Eagle Vision) can be found behind the upper arch.

15

John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice:

The two most refined buildings in this style in Venice are, the small Church of the Miracoli, and the Scuola di San Marco.

The Scuola Grande di San Marco — as I have said — was designed by Pietro Lombardo. The Church of the Miracoli — I say now — was also designed by him.

If I blame Pietro Lombardo for Tito’s cerebral palsy, I should lay equal blame at the door of John Ruskin, who handed me all the necessary clues for interpreting the architecture of Pietro Lombardo. Standing contemplating the Scuola Grande di San Marco, just moments before entering the hospital in Venice, I could see only what John Ruskin had seen before me.

16

What John Ruskin, with his Eagle Vision, saw before I ever did:

The method of inlaying marble, and the general forms of shaft and arch, were adopted from the buildings of the twelfth century.

The Scuola Grande di San Marco, which harked back nostalgically to the twelfth century, fitted in with what John Ruskin, in The Stones of Venice, called the Byzantine Renaissance.

For John Ruskin, as for me, the best thing about Pietro Lombardo was precisely that regressive tendency. For John Ruskin, as for me, the best thing about Pietro Lombardo was his contrarian reactionaryism.

17

In 1853, John Ruskin published the third and final volume of The Stones of Venice, entitled The Fall.

The architecture of a place, according to him, had the power to shape the destiny of its inhabitants. The Byzantine architecture of the twelfth century and the Gothic Byzantine architecture of the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth centuries had determined the intellectual and moral superiority of the Venetians, ensuring their commercial and military hegemony. On the other hand, Renaissance architecture, which drove out Gothic Byzantine architecture from the sixteenth century onward, represented an age corrupted by the sense of pride. The same sense of pride that, again according to John Ruskin, finally ruined the city, relegating it to a long period of decline.

Yes: The Fall.

John Ruskin pointed out the most harmful elements — or the “immoral elements” that went against the “law of the Spirit” — apparent in the architecture of the Renaissance: Pride of Science, Pride of State and Pride of System.

18

If, as John Ruskin argued, the architecture of a place really does have the power to shape the destiny of its inhabitants, then I could say that the façade of the Scuola Grande di San Marco shaped the birth of Tito.

With its pilasters, its assymetrical arches, its grotesque ornamentation, its colored marble, the Scuola Grande di San Marco harked back to a Byzantine past, untouched by that Renaissance sense of Pride.

To go back to John Ruskin: the architecture of Pietro Lombardo, in the form of the façade of the Scuola Grande di San Marco, exalted the “law of the Spirit,” rejecting Pride of Science, Pride of State and Pride of System.

The same could be said of Tito’s birth.

Pride of Science? A medical mistake caused his cerebral palsy. Pride of State? Venice Hospital is publicly owned. Pride of System? The system, with its rules, regulations and procedures, failed — failed repeatedly — during Tito’s birth.

19

(Picture Credit 1.3)

20

In the previous image: Le Corbusier as Ezio Auditore da Firenze, posing outside the Scuola Grande di San Marco, poised to destroy the architecture of Pietro Lombardo.

Yes: The Fall.

21

I was born on 22 September 1962.

On that same day, Le Corbusier received an invitation to design a new hospital for Venice, with the hospital being moved from the Scuola Grande di San Marco to the site of the slaughterhouse of San Giobbe.

An event that occurred on the day of my birth could, therefore, have changed Tito’s birth.

That’s what Tito’s story is like: circular.

22

According to Le Corbusier, the streets and squares of Venice resembled the cardiovascular system, with its arteries and ventricles.

The hospital he designed was based on that model, being a kind of great cardiovascular system, comprising a series of terrifying reinforced concrete blocks, joined by a network of ramps and bridges.

Six months after presenting his project, Le Corbusier walked into the sea and died. The reinforced concrete arteries and ventricles of his cardiovascular system stopped working at an opportune moment.

His plan for a new Venice Hospital was buried.

23

Good, represented by the architecture of Pietro Lombardo, generated Evil, represented by a mistake at birth. And Evil, represented by the architecture of Le Corbusier, would have generated Good, because his project for a new Venice Hospital would have been carried out and I would have chosen another place for Tito to be born.

24

Now we live in Rio de Janeiro.

Tito walks on Ipanema beach every day. Today he took two hundred and eighteen steps without falling. Then he fell. He always falls. The sand cushions his fall. He can fall over without grazing his knees or smashing his teeth.

Just like the Scuola Grande di San Marco, Tito’s spasticity harks back to the past, paralyzing his motor maturation. I love every Byzantine detail of his motricity.

As with the Scuola Grande di San Marco, Tito is trying to resist the fall. But he always falls. And he always laughs when he falls.

25

26

In the previous image: one of the two hundred and eighteen steps Tito took on Ipanema beach.

27

My words to Anna, as we stood contemplating the Scuola Grande di San Marco, moments before entering Venice Hospital, came true: “With a façade like that, I could even accept having a deformed child.”

I accepted Tito’s cerebral palsy.

I accepted it as if it were the most natural thin

g in the world. I accepted it with delight. I accepted it with enthusiasm. I accepted it with love.

28

On the day Tito was born, Anna and I walked through the gate of the Scuola Grande di San Marco and crossed what used to be the atrium.

29

For more than five hundred years, the Scuola Grande di San Marco was the largest lay confraternity in Venice.

As well as taking in its members when they fell ill or slid into poverty, it also took in the poorest of the city’s inhabitants — into that very atrium — guaranteeing them vital support in times of epidemic, scarcity and war.

30

Napoleon Bonaparte occupied Venice in 1797. Some time later, he crowned himself its emperor.

One of his first acts was to suppress the confraternity of the Scuola Grande di San Marco and transform the building into a military hospital.

Napoleon Bonaparte’s military hospital, which opened in 1808, was the predecessor of the state hospital where Tito would be born.

31

I blame Pietro Lombardo and John Ruskin for Tito’s cerebral palsy.

I also blame Napoleon Bonaparte, without whom the Scuola Grande di San Marco would never have become Venice Hospital.

The Fall of the Bastille resulted in the Fall of La Serenissima. The Fall of La Serenissima resulted in Tito’s many falls.

32

33

In the previous image: the Fall of the Bastille.

The Fall

The Fall