- Home

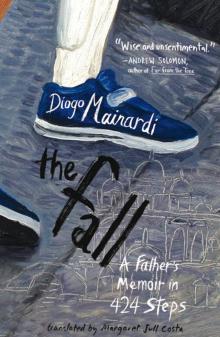

- Diogo Mainardi

The Fall Page 3

The Fall Read online

Page 3

That’s what Tito’s story is like: circular.

77

The cloister in which I saw Tito for the first time, in an incubator, with his face green, belonged to the former Dominican monastery.

On that night, Anna and I slept in one of its rooms.

Tito remained alone in the neonatal intensive-care unit in Padua Hospital, suffering convulsions.

78

The following day, before going to Padua Hospital, I popped into the patisserie Rosa Salva, in Campo Santi Giovanni e Paolo, opposite the Scuola Grande di San Marco.

One of the reasons I had insisted that Tito be born in Venice Hospital, apart from Pietro Lombardo’s architecture, was the proximity of the patisserie Rosa Salva.

To go back to Tommaso Rangone: the food that proved most harmful to Tito’s health — the one that nearly killed him in the womb — was the bigné allo spumone di zabaione.

79

80

In the previous image: a bigné allo spumone di zabaione.

I blame Tito’s cerebral palsy on Pietro Lombardo, John Ruskin, Napoleon Bonaparte, an amnihook, and, lastly, on the bigné allo spumone di zabaione made by the patisserie Rosa Salva.

81

I arrived early at the intensive-care unit in Padua Hospital.

Tito was in an incubator. He lay utterly still. A tube hung from an artery in his foot. Another tube, attached to a ventilator, made one nostril grotesquely large. His body was covered with electrodes connected to a series of machines. Occasionally, one of those machines gave an alarm signal, and the doctors in the unit would rush over to check what was happening. Whenever they did, I was gripped by the fear that Tito might be dying. That fear filled me with both despair and relief, because I could only be sure that Tito was still alive when I feared that he was dying.

In order to die, Tito had to be alive.

82

I spent the day in the intensive-care unit.

I stroked Tito’s face. Still dead. I stroked Tito’s chest. Still dead. I stroked Tito’s leg. Still dead. I stroked Tito’s back. But when I stroked his back, the unexpected happened. He suddenly writhed and arched his spine.

Tito had returned to life.

I cried for half an hour. After crying for half an hour, I cried for another hour. After crying for an hour, I cried for another two hours.

83

The following day, I again visited the intensive-care unit at Padua Hospital.

I immediately stroked Tito’s back. He arched his spine even more than he had on the previous day.

I cried for two hours.

When I stopped crying, I remembered the scene in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein when the monster, lying in his tomb, receives an electric shock, violently arches his back and comes to life.

Tito came to life just like Frankenstein’s monster.

I cried for another two hours.

84

That night, returning alone on the train to Venice, I realized that each episode of my life corresponded to an Abbott and Costello sketch.

85

Gianni and Pinotto.

That’s what the Italians call Abbott and Costello.

They translated Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein as Gianni e Pinotto e il cervello di Frankenstein.

During the week I spent at the intensive-care unit in Padua Hospital, my sole interest was that: il cervello di Tito.

Or: Tito’s brain.

86

In Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, Count Dracula, played by Bela Lugosi, wants to transplant Lou Costello’s brain into Frankenstein’s monster, played by Glenn Strange.

It worked with Tito.

After his experience in Dottoressa F’s laboratory in Venice Hospital, he went on to combine the lack of motor control of Frankenstein’s monster with Lou Costello’s buffoonish nature.

87

In Padua Hospital, il cervello di Tito was analyzed using ultrasound, electroencephalograms and MRI scans.

No abnormalities were detected.

Up until now, no machine has uncovered the origin of his cerebral palsy.

88

Lou Costello in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein: “I’ve had this brain for thirty years. It hasn’t done me any good.”

89

(Picture Credit 1.7)

90

In the previous image: Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein.

Glenn Strange is the monster: deformed, ungainly, spastic, green.

91

In 1939, Adolf Hitler received a letter from Richard Kretschmar, a farmhand from Leipzig.

Richard Kretschmar begged Adolf Hitler to help him kill what he, in the letter, called a “monster.”

The “monster” was Richard Kretschmar’s own son, Gerhard Kretschmar.

Gerhard Kretschmar had been born blind, as well as missing a leg and part of his arm. He had also, according to his father, been born an “idiot.”

92

Adolf Hitler ordered his personal physician, Karl Brandt, to go to Leipzig University and examine Gerhard Kretschmar for himself.

At the Nuremberg Trials, Karl Brandt gave his own account of events: “If the facts given by the father proved to be true, I was to inform the doctors that, in Hitler’s name, they could use euthanasia.”

93

After examining Gerhard Kretschmar, Karl Brandt authorized his death.

On 25 July 1939, at the age of five months, Gerhard Kretschmar — blind and with a leg and part of his arm missing and, according to his father, an idiot — was executed with a large dose of the barbiturate Luminal.

94

In a statement made thirty years later, Gerhard Kretschmar’s father, Richard Kretschmar, recalled the “euthanasia” of his “monster” in these terms:

Karl Brandt explained to me that the Führer was very, very interested in my son’s case. The Führer wanted to solve the problem of people who had no future, whose lives were worthless. That is why he had granted a merciful death to our son. Later on, we would be able to have other perfectly healthy children of whom the Reich would be proud.

An example of Pride of State?

95

Four weeks after the murder of Gerhard Kretschmar, Adolf Hitler’s Ministry of the Interior determined that all disabled newborns should be reported to the regime’s authorities.

The Ministry of the Interior’s rules mentioned in particular those children suffering from “mongolism, microcephaly, hydrocephalus, deformities of the limbs or spine, and paralysis, including spasticity.”

That’s right: Tito.

96

On 1 September 1939, the Second World War began.

On the same day, Adolf Hitler signed a secret memorandum setting out his euthanasia program.

The memorandum gave doctors the power to “decide whether those who have — as far as can be humanly determined — incurable illnesses can, after the most careful evaluation, be granted a merciful death.”

97

Mercy killing. Gnadentod.

Euthanasia. Euthanasie.

Those were some of the terms used by Nazism to legitimize the mass extermination of disabled newborns.

A worthless life. Unwertes Leben.

A life not worth living. Lebensunwerten Leben.

Adolf Hitler’s “euthanasia” program offered “mercy killings” to those whose lives were “worthless” or “not worth living.”

98

99

In the previous image: the memorandum signed by Adolf Hitler, granting a mercy killing for Tito.

100

In the first phase of Adolf Hitler’s euthanasia program, five thousand disabled newborns were killed.

The historian Robert Jay Lifton published the testimony of one of the doctors responsible for those deaths, identified simply as Doktor F: “Those who were approved for killing received high doses of Luminal. They were spastic children, incapable of talking or walking. Anyone seeing them would imagine they wer

e sleeping. In fact, they were being killed.”

101

After he was born, Tito was taken into the intensive-care unit of Padua Hospital, where he received high doses of Luminal. Anyone seeing him would imagine he was sleeping. In fact, he was being brought back to life.

102

Adolf Hitler’s involuntary euthanasia program, known as Action T4, quickly widened its scope. As well as exterminating disabled newborns, it went on, in its second phase, to exterminate disabled adults, the mentally ill, epileptics and alcoholics.

Six hospitals were converted into extermination centers, where the doctors were charged with eliminating patients by injecting them with a mixture of morphine, scopolamine, curare and cyanide.

103

104

In the previous image: one of the children suffering from cerebral palsy who was selected to die under the Action T4 program.

105

In the first few months of 1940, in Brandenburg Hospital, Karl Brandt observed an experiment that would change the direction of the Action T4 program.

Twenty patients, confined in a place resembling a public shower room, were gassed to death with carbon monoxide.

Their bodies were immediately cremated by the SS.

106

When Karl Brandt reported back on the result of the Brandenburg experiment, Adolf Hitler decided that all the “biological enemies” of the Third Reich should be eliminated in the same way: gassed and cremated.

107

Biological enemies. Biologische Feinde.

Only “racial hygiene” could eliminate the “biological enemies” contaminating the Third Reich.

Racial hygiene. Rassenhygiene.

108

In the second quarter of 1940, Adolf Hitler’s Ministry of the Interior ordered that an inventory should be made of all Jews in the Action T4 program.

In June of that year, the first group of two hundred Jews, from a psychiatric hospital in Berlin, were gassed and cremated at Brandenburg Hospital.

109

The extermination of Gerhard Kretschmar — a disabled child rejected by his father — had become the extermination of a whole people: the Holocaust.

110

In less than two years, Action T4 killed more than a hundred thousand people.

Adolf Hitler stopped the program on 24 August 1941.

Two months later, the first large extermination camp, under the command of the SS, was opened near Chelmno, and there all the biological and ideological enemies of Germany, the disabled and the Jews, were gassed and cremated on an industrial scale.

In the following months, extermination camps were opened at Belzec, Sobibor, Majdanek, Treblinka and Auschwitz.

111

The administrator of Action T4, Franz Stangl, who was responsible for the deaths of thirty thousand disabled people at the euthanasia center of Schloss Hartheim, became the first commandant of the Sobibor extermination camp.

Between May and August 1942, he killed a hundred thousand Jews.

Franz Stangl was promoted to the post of commandant at the extermination camp Treblinka II.

Between August 1942 and August 1943, he killed another eight hundred thousand Jews.

112

After the fall of the Third Reich, Franz Stangl fled to Brazil.

Pursued by Simon Wiesenthal, he was arrested on 28 February 1967 and extradited to Germany.

Found guilty of the deaths of more than nine hundred thousand people — among them the cerebral palsy sufferers from Action T4 and the Jews from Operation Reinhard — he died in his cell in Düsseldorf.

113

Like Franz Stangl, Josef Mengele also fled to Brazil.

As an SS doctor, he was charged with examining and selecting the prisoners from the Auschwitz extermination camp.

The able-bodied — who could be used for slave labor — were sent to his right. The less able-bodied — who could be immediately gassed and cremated — were sent to his left.

114

(Picture Credit 1.8)

115

In the previous image: Josef Mengele in Auschwitz selects those who will live and those who will die.

The photo was taken in 1944.

116

In Auschwitz, Josef Mengele conducted medical experiments that resulted in the disability or death of thousands of prisoners.

Educated at the Institute of Racial Hygiene in Frankfurt, he had a particular interest in hereditary anomalies, such as dwarfism, hermaphroditism and Down’s syndrome. According to him, Judaism itself was a hereditary anomaly. In their natural state, all Jews were “monsters.” And all “monsters” were Jews.

117

In one of his experiments, Josef Mengele selected two boys — one of whom was disabled — and cut them in half lengthways with a scalpel.

Then he sewed one child to the other: back to back, shoulder to shoulder, wrist to wrist — as if they were Siamese twins.

One of the boys was called Nino. The other boy was called Tito.

That’s right: Tito.

118

Tito and Nino.

My sons are called Tito and Nico.

119

We are on Enseada beach in Bertioga.

On 7 February 1979, Josef Mengele waded into the sea on Enseada beach, had a brain hemorrhage and died.

I have come here with my sons Tito and Nico, on the trail of Josef Mengele. I want to wade into the sea in which he died. I want to dance on his corpse. I want to celebrate the value of the life of a disabled son.

I am the Simon Wiesenthal of cerebral palsy.

Josef Mengele is dead. Tito is alive.

120

On Enseada beach, I blow up some water wings.

Tito — the monster — wades into the sea. Nico goes with him.

Tito and Nico: one is sewn to the other.

121

122

In the previous image: my Siamese twins.

123

Tito improved rapidly at Padua Hospital.

On the second day of his life, he stopped having convulsions.

On the third day of his life, he could breathe without the help of machines.

On the fourth day of his life, he uttered a sound that the doctors interpreted as crying. On the fifth day of his life, he opened his eyes wide. On the sixth day of life, he took milk from the breast. On the seventh day of life, he was discharged from the neonatal intensive-care unit and placed in a room with my wife.

124

A week later, Tito came home.

125

We lived in the Palazzo Barbaro Wolkoff on the Grand Canal, next to the Palazzo Dario.

Who designed the Palazzo Dario?

That’s right: Pietro Lombardo.

126

(Picture Credit 1.9)

127

In the previous image: the Palazzo Barbaro Wolkoff, where we lived, and to its right the Palazzo Dario.

The painting is by Claude Monet. It dates from 1908.

I am at the window, cradling Tito and looking out over the Grand Canal.

128

Claude Monet stayed in Venice two and a half months.

When he painted my windows, his wife, Alice, wrote in a letter to her daughter Germaine:

He’s doing some marvellous work and, between you and me, it’s a welcome change from those old water lilies.

129

I am the Claude Monet of cerebral palsy. Tito is my water lily. He has become my sole subject matter. I devote myself entirely to him, he is my one passion. I never tire of my subject matter either. I always find in him an unexpected color, an unexplored shadow. Tito is the Absolute. Tito is Everything.

130

Pietro Lombardo designed the Palazzo Dario in 1486.

In the same year, Jacopo Sansovino was born.

Like Pietro Lombardo, Jacopo Sansovino is linked in circular fashion to Tito’s birth. First, he designed one wing of the Scuola Grande di San Marco, completing Pietro Lombardo

’s work. Then he designed the Church of San Giuliano, adorning its doorway with a statue of Tommaso Rangone. Finally, he designed the Palazzo Corner, opposite the Palazzo Dario and the Palazzo Barbaro Wolkoff, on the other side of the Grand Canal.

I could see the Palazzo Dario and the Palazzo Corner from my window.

131

(Picture Credit 1.10)

132

In the previous image: on the right, the Palazzo Dario, designed by Pietro Lombardo, and on the left the Palazzo Corner, designed by Jacopo Sansovino.

The painting is by Canaletto. It dates from 1738.

I am still at the same window, cradling Tito and looking out over the Grand Canal.

133

According to John Ruskin, the Palazzo Dario is an “exquisite example” of the domestic architecture of the time. The Palazzo Corner, on the other hand, built half a century later, in 1537, was “one of the worst and coldest buildings of the central Renaissance.”

The Palazzo Dario expressed the soul of a true artist like Pietro Lombardo, who could also reason, but only occasionally, and who could even acquire knowledge, but only the knowledge he could pick up “without stooping, or reach without pains.” The Palazzo Corner, on the other hand, expressed Jacopo Sansovino’s academic pride, along with his geometrical fanaticism, which could “be taught to any schoolboy in a week.”

The Palazzo Dario was “good for God’s worship.” The Palazzo Corner was “good for man’s worship.”

The Fall

The Fall