- Home

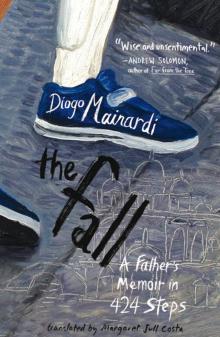

- Diogo Mainardi

The Fall Page 5

The Fall Read online

Page 5

My wife and I enthusiastically accompanied Tito’s gymnastics.

We were happy in that place. We were as united as two old Jewish suicides.

184

185

In the previous image: Tito and his Bobath therapist.

186

Neil Young has two children with cerebral palsy.

That’s right: two.

He is my guru.

187

Neil Young’s first child, from his first marriage, is called Zeke. Neil Young’s second child, from his second marriage, is called Ben.

Zeke was born in 1972. He has a mild case of cerebral palsy.

Ben was born in 1978. He has a severe case of cerebral palsy.

188

When Ben was two years old, Neil Young and his wife took him to the Institutes for the Achievement of Human Potential.

The Institutes for the Achievement of Human Potential persuaded them to devote all their time to Ben’s treatment, giving him twelve hours of physiotherapy a day, seven days a week.

189

The Institutes for the Achievement of Human Potential is a sect.

If Neil Young is my guru, the guru of the Institutes for the Achievement of Human Potential is Glenn Doman.

According to Glenn Doman, a child with cerebral palsy needs to be continually manipulated by his parents, because if he keeps passively repeating a series of standardized movements over a long period of time, his brain will change and replace the damaged parts.

190

In 1981, Neil Young recorded a song about Ben’s treatment using Glenn Doman’s method.

It’s “T-Bone” from the album Re-ac-tor.

It is the anthem of cerebral palsy.

191

In “T-Bone” Neil Young fanatically repeats the same two lines, for nine minutes and ten seconds, just as the physiotherapists at the Institutes for the Achievement of Human Potential told him to fanatically repeat Ben’s movements, twelve hours a day, seven days a week.

In the first line, repeated twenty-five times, Neil Young says, “Got mashed potatoes.” In the second line, repeated another twenty-five times, he says, “Ain’t got no T-bone.”

192

In 1989, some years after abandoning the Institutes for the Achievement of Human Potential, Neil Young, in an interview with the Village Voice Rock and Roll Quarterly, talked about Ben’s treatment following Glenn Doman’s method:

You manipulate the kid through a crawling pattern … He’s crawling down the hallway, he’s banging his head trying to crawl. But he can’t crawl, and these people have told us that if he didn’t make it, it was gonna be our fault … We lasted eighteen months. Eighteen months of not going out. Eighteen months of not doing anything.

193

In the last thirty years, the Institutes for the Achievement of Human Potential, with its stupid Lamarckian belief that passive, repetitive movement can mold the characteristics of children with cerebral palsy, changing their brains, has lost almost all its followers.

It was all mashed potatoes and no T-bone steak.

194

195

In the previous image: an egg.

Ben Young is now an egg producer. Instead of T-bone steaks, he has a farm in La Honda, with two hundred and fifty chickens.

196

During the treatment using Glenn Doman’s method, Neil Young and his wife moved Ben for twelve hours a day, seven days a week. While they did this, Ben remained completely passive.

With us it was the opposite.

Tito moved freely about the large apartment in which we were staying in Rio de Janeiro, going from room to room, twelve hours a day, seven days a week. While he did this, my wife and I watched in passive amazement.

Tito was our Glenn Doman. He changed our brains.

197

How did Tito move?

He had a ride-on car made by Chicco.

At first, he could only move the car backward. In time, he learned how to move the car forward and sideways, pressing down with his two feet at once.

When Tito started to pick up speed and fall over sideways, we fitted the car with two horizontal bars to give him more stability. When he started to pick up even more speed and to fall forward, performing a somersault, we came up with the idea of screwing another wheel onto the front of the car.

Tito’s falls had become as spectacular as Lou Costello’s.

198

The greatest obstacle to a child with cerebral palsy is the impossibility of discovering the world around him.

With his Chicco car, Tito partially overcame that obstacle.

He would go into wardrobes and take the socks out of the drawers. He would go into the kitchen and tug at the cook’s apron. He would pass underneath the ping-pong table while we were having a game. He would go into the bathroom and drag the roll of toilet paper around the whole apartment.

Tito was discovering the world. We were discovering Tito discovering the world.

199

200

In the previous image: Tito in his car.

The toy car was Tito’s second mode of transport.

201

As time passed, Tito’s cerebral palsy became more and more obvious.

Other boys his age were running around and talking. He remained harnessed to the past, trying to crawl. His body was mutinying against his brain. His brain gave an order, his body disobeyed.

Tito was Dr. Strangelove, always trying to strangle himself.

202

At seven months, Tito was simply a person we loved. At eighteen months, he had already become a person with cerebral palsy whom we loved.

We loved Tito so much that we even loved cerebral palsy.

203

I quote from the column I published on 24 June 2002:

There is no more thrilling adventure than having a child with cerebral palsy. The worst enemy for a child with cerebral palsy is gravity. It’s as if he were being permanently pursued by some crazed judo player who enjoys tripping him up. What he needs most of all is to learn how to fall. Then he’ll leap from white belt to yellow belt, from yellow belt to red belt, until he reaches his limit. All the motor abilities that we acquire automatically, instinctively, he is trying to acquire through discipline, method, thought. It’s the struggle of the intellect against savage nature. The perfect metaphor for the history of humanity. David and Goliath. Theseus and the Minotaur. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

204

(Picture Credit 1.13)

205

In the previous image: one of the sixteen falls made by Lou Costello in Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

No one falls better than Lou Costello.

206

I ended that column published on 24 June 2002 in shamelessly sentimental fashion. I loved Tito. I loved cerebral palsy.

When people learn that my son has cerebral palsy, they look at him with a mixture of sympathy and pity. I look at him as if he were a totem: with devotion, reverence and a feeling of inferiority. They say that a child with cerebral palsy is better suited for living on the Moon, where there’s no gravity. My son, therefore, is a man of the future, ready for interplanetary travel. You doubtless remember the Star Trek episode in which the aliens from a distant galaxy think that Captain Kirk is God? Well, I’m just like those aliens, and my son is Captain Kirk.

207

Apart from saying that Tito was God, I also said that “a child with cerebral palsy is like Newton’s apple: when he falls, he reveals the world’s secret mechanisms.”

208

Tito was my Law of Gravity. He was the principle by which I began to measure reality.

209

In the early years of his career as a neurologist, Sigmund Freud devoted himself to the study of cerebral palsy.

In 1897, he published his main work on the subject, entitled Infantile Cerebral Paralysis.

At the time, Sigmund Freud was entirely immersed in his research into neurose

s. In one of his letters, he remarked:

I am working on a study of infantile paralysis,

a subject that doesn’t interest me in the least.

210

Unlike Sigmund Freud, I was entirely immersed in my research into cerebral palsy, and neuroses didn’t interest me in the least.

211

In the second half of 2003, we took Tito to a neurologist in Boston.

212

213

In the previous image: Tito in Boston.

214

We spent six weeks in Boston, in an apartment in Back Bay.

After examining Tito, the neurologist handed him over to his team of doctors.

215

The Boston doctors gave Tito a general anesthetic in order to inject Botox into his legs. The Botox proved useless. The Boston doctors gave Tito another general anaesthetic in order to give him an MRI scan. The MRI scan proved useless. The Boston doctors took a mold of Tito’s legs in order to make him a pair of orthopedic leg calipers. The orthopedic leg calipers broke as soon as we got back to Rio, and they were thrown out. The Boston doctors made us order a walking frame. The walking frame wasn’t right for Tito at all.

216

I spent thirty thousand dollars in Boston.

Tito’s cerebral palsy cost me a lot of money.

217

Despite everything, I remember those six weeks in the apartment in Back Bay as a period of intense — almost irrational — happiness.

Because we were together. Because we were united. At that moment, I had the moral certainty of a fanatic. I had given up all my personal needs for something much bigger than myself. I worshipped Tito. Cerebral palsy was my sect.

218

The neurologist in Boston was useful in one respect.

He explained why, on his third birthday, Tito could still not say a single word.

He had dyspraxia.

219

The neurologist in Boston was useful in another respect as well.

He recommended that, in order to express himself, Tito should start using a digital communication device.

220

221

In the previous image: Tito and his Tech/Speak communication device.

222

The subject of “T-Bone” is Neil Young’s obsessive attempt to give Ben some sort of mobility.

The subject of “Transformer Man,” which is part of his next album, Trans, released in 1982, is Neil Young’s obsessive attempt to communicate with Ben.

223

Neil Young used a vocoder to distort his voice on “Transformer Man.”

He said:

Trans is the beginning of my search for communication with a severely handicapped non-oral person. “Transformer Man” is a song for my kid … People completely misunderstood Trans … Well, fuck them … You gotta realize — you can’t understand the words on Trans, and I can’t understand my son’s words.

224

“Transformer Man” is Neil Young’s worst song.

It’s deformed, unfinished, scarce half made up. It’s disproportioned in every part. It’s a foul bunch-backed toad. It’s a bloody dog.

I find the very awfulness of “Transformer Man” moving.

225

Neil Young’s albums about Ben’s cerebral palsy were the biggest commercial flops of his career.

Cerebral palsy cost him a fortune.

226

In “Transformer Man,” Neil Young offers a glimpse of a robotized world in which a spastic child, incapable of speech, can interact by using technology.

What his spasticity prevented him from doing alone, he would, in the future, be able to do using machines and by “pressing a button.”

227

228

In the previous image: the Transformer toy made by Hasbro twenty-nine years after Neil Young released his song “Transformer Man” and sold under the name of “Spastic.”

The future glimpsed by Neil Young was made real in the robotized world of the Power Core Combiners.

229

I wrote a column about Neil Young’s “Transformer Man.”

Neil Young had a collection of electric trains. Because his son Ben was incapable of making the trains run, Neil Young invented a gadget to help. The gadget was patented as the Big Red Button. With the Big Red Button, Ben was finally able to open gates, couple locomotives, make the train change track, let off steam and whistle.

230

I ended the column by speaking again about Tito:

My son was never interested in electric trains, but he has a Big Red Button connected to me. He turns me on and off whenever he wants. He makes me change track, let off steam and whistle.

231

Neil Young felt “electrified” by Ben.

I felt electrified by Tito. He was my “Transformer Man.” By pressing the buttons of his communicator, he could finally talk to me.

232

233

In the previous image: the button Tito had to press on his communicator to signal a fall.

That’s right: The Fall.

234

Tito’s communicator was made up of thirty-two windows. Each window contained a symbol that corresponded to a word or phrase. When Tito pressed the symbol, the communicator would emit a recording of that word or phrase. Since the communicator had six channels, Tito had at his permanent disposal one hundred and ninety-two recorded messages.

235

The messages on Tito’s communicator were recorded using my voice. He started speaking through me, distorting my words. Tito’s communicator was my vocoder.

236

Tito’s therapists were always adding new symbols to his communicator. He acquired a vocabulary of more than one thousand words, which accompanied him at all times.

When Tito was in a hurry, he would press the symbol of a rabbit. When he had diarrhea, he would press the symbol of a person sitting on the toilet. When he wanted to repeat something, he would press the symbol of two parallel arrows. When he was frightened, he would press the symbol of a green ghost. When he wanted to ask a question, he would press the symbol of a little man with an egg-shaped face raising one finger. When he was annoyed, he would press the symbol of a little man with an egg-shaped face with steam coming out of his ears. When he was bored, he would press the symbol of the little man with an egg-shaped face leaning on one elbow.

237

Tito could communicate only through images, gestures, symbols, metaphors and analogies.

I had to interpret this. I had to adapt to his language. If he used images, I had to use images. If he used analogies, I had to use analogies.

That is how Tito became my God, my Law of Gravity, my Auschwitz survivor, my turtle, my water lily, my Lou Costello, my Richard III, my James Stewart, my Fall of the Bastille, my Jacopo Tintoretto, my Scuola Grande di San Marco.

238

Tito was the result of everything I had seen and read. In particular, he was the result of everything I loved.

239

At Christmas, in 2003, Tito was given a Kaye Walker.

240

241

In the previous image: the button Tito had to press on his communicator to ask for the walker.

242

Tito is now on his fourth Kaye Walker.

It’s exactly the same model as the first, only larger.

Of all Tito’s various modes of transport, the walker is the most valuable. He still uses it today to walk down the street. He will probably always have to use it.

243

Initially, Tito could take only one or two steps with the walker. He had to move in a straight line, because the wheels were locked in that position.

Around the middle of 2004, when Tito was getting better at controlling the walker, his therapist released the front wheels and I started walking with him in the underground garage of the building where we were living, in Avenida Vieira Souto, in Ipanema.

The garage was spacious

and deserted. The floor was flat and smooth.

244

After exploring the garage, Tito became more confident and we set off to explore the garage of the building to the right. After exploring the garage of the building to the right, we went and explored the garage of the building to the left. Then, after exploring the garage of the building to the left, we explored the garages of dozens of other buildings in Avenida Vieira Souto.

245

Up until then, my sole talent had been my ability to leave Brazil; now, for the first time in my life, I was happy to be back in my native land.

The Fall

The Fall